Accessing the Infinite Light through the Kohen Gadol

Yom Kippur and the Power of Atonement

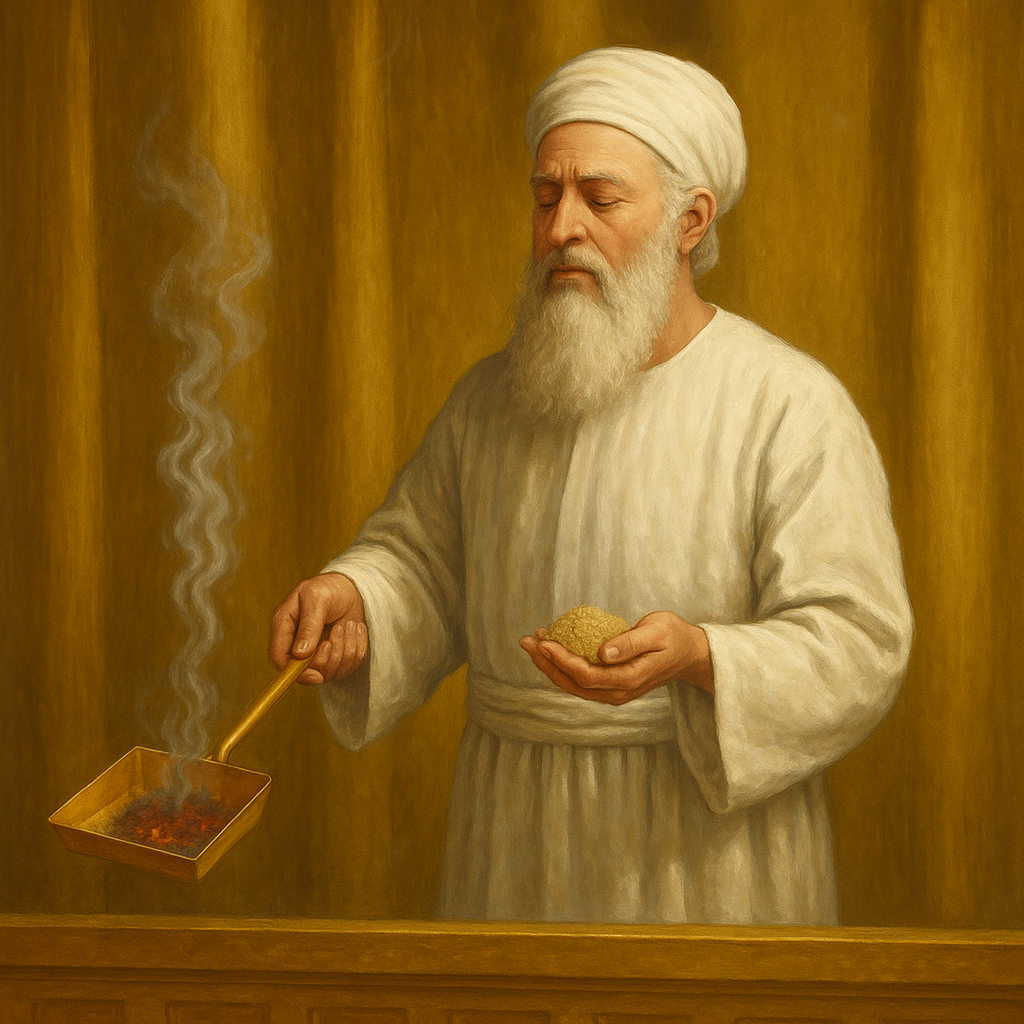

The Parshah begins with a detailed description of the Yom Kippur service. This one day a year, the Kohen Gadol is permitted to enter the Holy of Holies to achieve atonement for the entire Jewish people. This sacred space, though physical, serves as a connection point to the Infinite Light—Ohr Ein Sof.

Reb Noson, in his discourses based on Likutey Moharan Lesson 24, highlights that this atonement isn’t just a ritual cleansing. The Kohen Gadol’s access to the Infinite Light allows him to reach a spiritual level beyond time and space. From there, he draws forgiveness for sins committed since the previous Yom Kippur.

The Ten Days and the Keter

Reb Noson explains that the ten days from Rosh Hashanah to Yom Kippur correspond to the three intellectual faculties—Chochmah, Binah, and Da’at—each multiplied by the others, yielding nine spiritual chambers. The tenth day, Yom Kippur, is the Keter itself: the crown, the gateway to the Infinite Light. This is the highest level one can reach, where teshuvah (repentance) and atonement truly begin.

Only the Tzaddik Can Enter

The ability to effect atonement on this level requires a tzaddik—specifically the Kohen Gadol—who is worthy to enter this exalted place. Just as the Kohen Gadol must be spiritually pure and exceptionally holy to perform the Yom Kippur service, so too, each generation requires a tzaddik who can elevate us, even from our lowest places, by connecting to the light beyond understanding.

In and Out: The Kohen Gadol’s Movements

Another feature of the Yom Kippur service is the Kohen Gadol’s repeated movement in and out of the Holy of Holies. Each time he exits and reenters, he must change between the four white garments worn for entering the Kodesh HaKodashim and the eight garments used for standard services. Each change requires immersion in a mikveh.

This repetitive going in and out reflects the rhythm of Divine perception described in Likutey Moharan 24: the human mind must be allowed to run and return, to perceive and then step back. Constant advancement without pause would overwhelm a person. This is mirrored in the Kohen Gadol’s avodah—moments of direct contact with the Infinite Light, followed by retreats into structured service.

The Ascent Within the Descent: The Kohen Gadol’s Mikveh Immersions

Why Immerse on the Way Down?

Reb Noson raises a striking question. It’s understandable why the Kohen Gadol would immerse in the mikveh when transitioning from the regular daily service—performed in the eight garments—to the elevated Yom Kippur service, which required four white garments and entry into the Holy of Holies. Immersion symbolizes elevation, a spiritual ascent. Just like a woman immerses to rise from the impurity of niddah or a man purifies before prayer, the Kohen prepares to ascend.

But why, Reb Noson asks, must the Kohen immerse again when leaving the Holy of Holies and returning to the daily service? If he’s leaving a higher level and going “down,” what purpose does the mikveh serve?

Descending to Build Vessels

The descent after perceiving holiness is not a fall—it’s an essential part of growth. Rebbe Nachman teaches that the soul’s path is not linear. It is marked by ratzo v’shov (running and returning), matei velo matei (touching and not touching), advancement followed by restraint. The “descent” is what allows a person to internalize the light they’ve accessed.

The Kohen Gadol exits the Holy of Holies, and before returning to his “lower” tasks, he immerses again because he’s about to carry the impact of the Infinite Light into the world of action. It’s a descent for the sake of an even greater ascent. The going out is an aliyah.

Throughout the year, we face setbacks, failures, and confusion, but we remember: the journey in and out is part of the process.

The Goat to Azazel and the Power of Teshuvah

Atonement Beyond Logic

Another striking element of Yom Kippur is the ritual of the goat sent to Azazel. Unlike the korbanot offered on the altar, this goat is not slaughtered as a sacrifice. Instead, it is led deep into the wilderness, to a rocky cliff, and pushed backwards—symbolizing a complete rejection of the sins it represents. A crimson thread is tied to its horns, with a corresponding piece tied to the entrance of the Temple. When the goat reaches its end, if the crimson thread turns white, it’s a sign from Heaven that the Jewish people have achieved atonement.

Confession and the Scapegoat

Before this ritual, the Kohen Gadol offers multiple verbal confessions—first for himself, then for the Kohanim, and then for the entire nation. These verbal admissions, along with the sacrifices and incense, culminate in this deeply symbolic act of sending away sin. The scapegoat ritual emphasizes that there is an element of teshuvah that defies our understanding. It doesn’t follow conventional rules of korban or kaparah. Instead, it embodies the idea that even sins with no atonement in standard frameworks can be elevated through connection to something beyond logic—something rooted in the Infinite Light.

Why the Azazel? Completing the Atonement Through Descent

A Shocking Ritual with a Hidden Depth

The ritual of sending the goat to Azazel seems, on the surface, cruel and extreme. From the perspective of animal rights or emotional sensitivity, pushing a goat off a cliff until it’s smashed to pieces sounds barbaric. But the Torah’s approach is deeply spiritual: this animal, unlike any other, is laden with the collective sins of the Jewish people.

Through the vidui (confession) spoken over it by the Kohen Gadol, the goat becomes a spiritual vessel carrying immense impurity. The Zohar explains that once it receives this weight of evil, the goat itself becomes a force for destruction. Letting it live would be a danger to the world. The only way to rectify the sins and purify the Jewish people is through this severe and final act.

From the Infinite Light to the Darkest Cliff

But if the Kohen Gadol already entered the Holy of Holies and accessed the Infinite Light, bringing about atonement through the incense and the blood offerings, why is this additional ritual necessary?

However, this reveals a powerful truth: the true test of elevation is what happens after the light. The Kohen Gadol must return from the holiest place on earth into the murky, confusing world. The realm called Heichal HaTemurot, the Chamber of Exchanges, represents the tangled mess of good and evil, clarity and confusion that makes up the human experience.

The Final Descent and the Role of Azazel

The smashing of the Azazel goat is the final act of descending into this concealment, where the good is buried inside the bad. It’s only through this process that the final sparks can be redeemed. The “inhumane” nature of the act is intentional—it reflects the harshness of evil and the necessity of extracting good from its grasp.

The entire Yom Kippur service teaches that true rectification doesn’t happen in the heights alone. It requires entering the light and returning to uplift the darkness. The Kohen Gadol’s in-and-out movement, his transitions between holier garments and the daily ones, between incense and animal sacrifice, is a model of spiritual balance.

Living the Yom Kippur Path Every Year

Even without the Temple, we relive these devotions on Yom Kippur. When we read the Avodah service in the Musaf prayer, bow down during the reciting of the Kohen Gadol’s service, and envision the ritual of Azazel, we activate remnants of that Infinite Light.

And throughout the year, as we face setbacks, failures, confusion, and the need to start again—we remember: the journey in and out is part of the process. The path of descent for the sake of ascent is embedded in the deepest rituals of our holiest day, and in our daily lives.

Shabbat Shalom

Meir Elkabas