Bringing Joy to the Lepers

The Spiritual Meaning of Tzara’at

Parshat Tazria and Metzora deal with the laws of tzara’at, a spiritual affliction. According to Rashi, tzara’at is the punishment for speaking lashon hara—slander. But the punishment goes far beyond the surface. Once declared impure by the Kohen, the metzora is exiled from all three camps in the desert: the Mishkan, the camp of the Levi’im, and the camp of Israel. He must dwell alone—“badad yeshev”—and even announce his impurity to others lest they draw near.

The Zohar explains that this person has experienced a segira denahora ila’ah—a closing of the supernal light. In the framework of Likutey Moharan Lesson 24, this means he’s been cut off from access to the infinite light. Why? Because lashon hara isn’t just a sin of speech—it reflects a much deeper internal problem: a soul disconnected from joy.

Lashon Hara Begins With Unhappiness

Why do people speak negatively about others? Rebbe Nachman teaches that someone who is unhappy with himself will inevitably start seeing others through the same negative lens. A person filled with simcha finds the good in others; someone disconnected from his own goodness becomes critical, negative, and eventually slanderous.

So at its root, lashon hara flows from a lack of simcha. A person who isn’t in touch with his own nekudah tovah—his small but real point of goodness—becomes jealous, cynical, and bloated with self-importance. This is what leads to the inflated ego and arrogant behavior that precedes lashon hara.

The Metzora’s Purification Process and the Root of the Sin

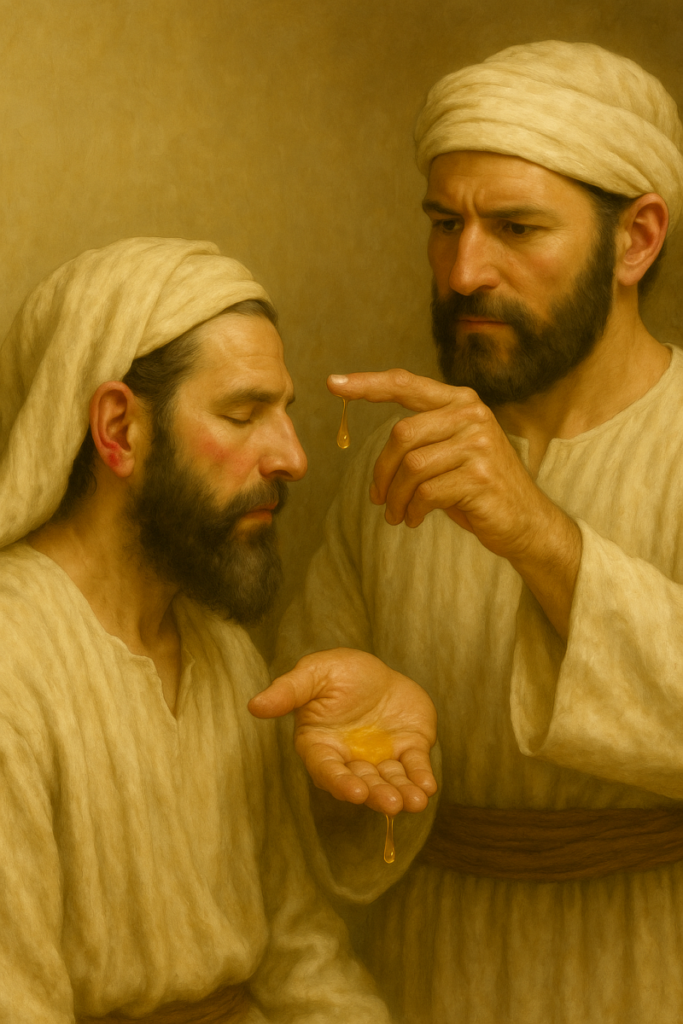

The Torah hints at the root of the problem in the metzora’s purification process. Once he begins to heal, the Kohen comes to check him, and a unique ritual follows: two birds are taken, one slaughtered and the other dipped in its blood along with a bundle of cedar wood (erez), hyssop (ezov), and crimson wool (tola’at). Rashi explains the symbolism: the cedar represents pride, while the hyssop and crimson wool—whose name tola’at also means “worm”—represent humility.

The metzora must confront the truth: his arrogance came from inner emptiness. He lacked joy in his good points and instead inflated himself to feel better. But rather than being uplifted, this arrogance led him to lash out at others, and ultimately to isolation—both spiritual and social.

Joy as the Key to Spiritual Elevation

In Likutey Moharan 24, Rebbe Nachman explains that joy is the foundation of spiritual growth. When a person performs mitzvot with simcha, it empowers the mitzvah to rise and draw blessing down into the world. That blessing then opens the gateway to the infinite light. But someone who is unhappy with himself cannot reach that simcha. He cannot lift his mitzvot or his life.

The metzora’s isolation reflects his internal spiritual blockage. Cut off from others, he is also cut off from divine light. Only when he humbles himself and begins to appreciate his own small goodness can he begin to return—both to the camp and to Hashem.

The Kohen as the Channel of Blessing

We can now understand more deeply the role of the Kohen in the process of tzara’at. The Kohen is central—not only in declaring the person impure but also in declaring him pure. This isn’t incidental. The Kohanim are the designated conduits of blessing in the world, as revealed through Birkat Kohanim—the Priestly Blessing. Their hands become vessels through which divine bracha flows, making every instance of Birkat Kohanim a profound spiritual moment.

In Likutey Moharan Lesson 24, Rebbe Nachman teaches that bracha is drawn through simcha. When a Jew performs a mitzvah with joy, it elevates the mitzvah and activates blessing, which in turn opens the way to higher levels of divine perception. The Kohen, as the one who embodies blessing, must therefore be the one to declare whether the leper—a person who lost access to blessing—is pure or impure. Only the Kohen, source of bracha, can restore it.

The Leper and the Root of His Fall

Why is the metzora sent outside all three camps? Why must he sit alone? The Torah wants him to internalize the message. As we saw earlier, the root of his lashon hara is haughtiness. And that haughtiness itself stems from a lack of joy. There is an oral tradition that Rebbe Nachman famously said, “I can help anyone except for a baal ga’avah.” A haughty person refuses help. He cannot receive guidance or correction because he is too full of himself. And until he humbles himself, no remedy can reach him.

Reb Noson explains this further by analyzing the Mishnah in Pirkei Avot: Kin’ah, ta’avah, and kavod remove a person from the world. A person might struggle with jealousy or desires and still be reachable. But once kavod—honor and haughtiness—is added to the mix, there’s no longer an opening. Haughtiness closes the door to teshuvah.

The Role of the Bird and the Crimson Wool

The purification ritual reflects this message vividly. One bird is slaughtered, and the other is dipped along with hyssop, a cedar branch, and crimson wool—a mix of opposites. The tall cedar represents arrogance; the hyssop and crimson wool (tola’at—also the word for worm) represent humility. The leper must internalize this contrast. He spoke excessive gossip, like a bird that chatters nonstop. He inflated himself like a tall cedar. Now he must bring these down into the lowliness of the hyssop and worm.

Falling Back as a Prerequisite for Ascent

Rebbe Nachman outlines a spiritual process in Lesson 24 that mirrors the leper’s journey. When a person serves Hashem with simcha, this simcha elevates his actions and draws bracha. The bracha leads him toward the Keter—the crown—which is the entryway to the infinite light. But the Keter pushes a person back. This betisha—the sudden recoil—is not a punishment, but a divine mechanism that forces humility. If the person receives the pushback with joy, sees it as Hashem’s message to slow down and internalize, and continues to serve with joy, he then builds the vessels that will later hold the infinite light.

Total Isolation: The Extreme Pushback

However, the leper is not just pushed back—he’s pushed all the way out. Total isolation. No one consoles him. No one encourages him. No books, no chavruta, no chizuk. Not even a rabbi. Why? Because the root of his fall—ga’avah, haughtiness—demands complete breakdown. Rebbe Nachman teaches that this kind of person must be forced into solitude. Only by being badad yeshev—completely alone—can he begin to truly humble himself and turn inward.

And what happens in that aloneness? The opportunity for hitbodedut—deep, personal prayer without distraction. The leper has to confront himself, with no one to blame, no support to lean on. Only in that place of true humility can he begin the path to purification.

The Kohen Returns: Renewal Begins

When the person has truly been humbled, the Kohen—the representative of blessing—comes out to him. The one who once declared him impure now comes to declare him pure. This initiates a long process of purification, culminating in korbanot and sprinkling the leper with both blood and oil.

One of the key rituals involves putting the blood of a korban on the leper’s right middle ear (the tenuch), right thumb (the bohen), and right big toe (also bohen). Afterward, the same three spots are anointed with oil.

Three Gateways: Feet, Hands, Ears

These three are symbolic of ascending spiritual levels:

- Feet: The feet represent movement—specifically, the momentum created when mitzvot are done with joy. Joy gives a mitzvah “legs”. Without simcha, the mitzvah remains static. With simcha, it runs upward.

- Hands: The hands are channels for bracha. The Kohanim bless with their hands, because the hands transmit divine energy. When a person brings joy into their service, they activate the “hands”—activating the flow of blessing.

- Ears: The ears connect to deep understanding. “The heart understands through the ears.” Once a person has activated joy and blessing, he can then begin to access spiritual insight and receive clarity.

So although the Kohen begins by applying the blood and oil from top to bottom, the true path of spiritual ascent works in the opposite order: from the feet (action with joy), to the hands (blessing), to the ears (understanding).

Slander comes from haughtiness, and haughtiness comes from not being happy with one’s good points

The Five Voices of Joy

This brings us back to the hei of simcha—the five pathways Rebbe Nachman reveals for attaining joy, rooted in the verse from the wedding blessings: Kol sason v’kol simcha, kol chatan v’kol kalah, kol omrim hodu la’Hashem ki tov.

These five kolot—voices—reflect five practical tools for generating joy:

- Jokes and silliness: Break the seriousness, shake yourself out of heaviness. Even forced humor has power.

- Music and movement: Dance, clap, sing, use nigunim to stir the soul.

- Finding good points: Locate the spark of goodness in yourself and others.

- Gratitude: Once you see the good, thank Hashem for it.

- Joy of the future: Even if the present is dark, be happy knowing that the Final Redemption is coming, and everything will turn out for the best.

Each of these five, Rebbe Nachman teaches, is a spiritual lever to restore joy—and from joy, the entire healing process begins.

Blood, Oil, and the Path to the Infinite Light

Once the leper has gone through the humiliation, the isolation, the personal hitbodedut and the sincere humility—now the Kohen returns to apply both blood and oil to the three key gateways: the ear, the thumb, and the big toe.

- Blood represents submission. When the blood is removed from an animal, its life force halts—symbolizing humility and hachna’ah. The Kohen places the blood on the leper’s ear, thumb, and toe to symbolize full-body submission, from understanding to action, to movement.

- Oil, especially olive oil from the Temple, represents simcha—joy. As the verse says, “Shemen u’ketoret yesamach lev”—“Oil and incense gladden the heart.” Joy is essential for spiritual ascent.

The Symbolism of the Body

Each point of application contains deep symbolic meaning:

- The foot represents mitzvah performance with momentum—joy in action. The pressure point of a person’s physical movement is the big toe. That’s where joy must be felt and expressed.

- The hand—specifically the thumb—represents the channel of bracha. The Kohanim bless with their hands. Joy in mitzvot awakens blessing.

- The ear is the gateway to understanding and connection with the infinite light. The ear must be infused with both humility (blood) and joy (oil).

The Kohen’s order—top to bottom—starts with the ears, to awaken da’at, and then moves downward, but Rebbe Nachman explains the actual spiritual path ascends from bottom to top: joy in action (feet), leads to blessing (hands), and ultimately perception and light (ears).

Bohen and Tenuch: Secret Codes

Even the names themselves hint to the journey:

- Bohen (the Hebrew word for both thumb and big toe) contains bet, hei, and nun:

- Bet for bracha—blessing,

- Hei for the five forms of joy,

- Nun for 50, alluding to the 50th gate of understanding—the Keter.

- Tenuch, the term for the middle of the ear, resembles Tanakh—the written Torah. This reminds us that true spiritual hearing begins with immersing in the Torah itself, the foundation for all spiritual growth.

The Core Lesson: Joy in the Small Things

All of this circles back to the source: slander comes from haughtiness, and haughtiness comes from not being happy with small good points. The leper is punished by being thrown out entirely, but that same isolation is what makes him capable of returning.

He learns to value the smallest sparks of good within himself—nekudot tovot. From there he rebuilds: joy → bracha → perception → Keter → infinite light.

Shabbat Shalom

Meir Elkabas