- Faith ⬦ Read ⬦ Shabbat ⬦ Weekly Torah Portion

It’s Always Better to Behave Cordially! – Parshat Kedoshim

There is a mitzvah of rebuke, but there are those who are overzealous in fulfilling this mitzvah, making up reasons why it is actually a mitzvah to persecute someone because he sinned and has become a regular transgressor. There is actually a proper and better way to do this, which is the topic of this week’s parsha discussion.

This week’s Torah portion is Parshat Kedoshim. Many commandments are given over in this parsha. Our sages taught about the verse, “Speak to the entire congregation of the children of Israel,” that “This teaches us that this passage was stated in the assembly [of the entire congregation of Israel] because most of the fundamental teachings of the Torah are dependent on it [i.e., they are encapsulated in this passage]” (Rashi on Leviticus 19:2). The Midrash also teaches that all of the Ten Commandments are included in this parsha.

One of the central topics in this parsha is the commandment to rebuke. It is a mitzvah to rebuke a Jewish person who is not behaving properly, to point out his mistake and guide him to the proper path. The Torah teaches: “You shall not hate your brother in your heart. You shall surely rebuke your fellow but be careful that you shouldn’t bear a sin on his account” (Leviticus 19:17).

Let us look closely at how this mitzvah is bundled together with the mitzvah of not hating our brother and not bearing a sin on his account. This means that we should not embarrass him, as Rashi explains: “but you shall not bear a sin on his account,”: i.e., in the course of your rebuking your fellow, do not embarrass him in public (Ibid.).

Rabbi Natan emphasizes that this teaching is especially necessary regarding this mitzvah because where there is machloket (controversy), it is easier to err more than in any other area and turn a sin into a mitzvah and evil into good. And this is precisely the reason that the Torah emphasizes that even when you rebuke your friend, you need to be careful that because of your rebuking him, “you shouldn’t bring a sin upon yourself,” which is what would happen were you to embarrass him in public.

In fact, there is a not-so-simple paradox involved in this issue: on the one hand, every Jew is obligated to act according to the laws of the Torah, and in general, all members of society need to behave in a proper and honest manner. The commandment of rebuking stems from the need to make a person aware of his mistake and to lead him to the correct path. Nowadays, it is commonplace to say that surely, we should behave towards this person “open-mindedly and with forbearance,” even when we see that his actual intention is to abandon all principles in order to permit everything for himself, G-d forbid. This is exactly what the Torah is rejecting. We are commanded to seek to maintain the highest standards of morality and decency at all times and to place them as a guiding principle, and not, G-d forbid, to give up on them or to treat them lightly, or even to assert that it is not our business what others do. On the contrary, all Jews are guarantors for one another, and what someone else does can also have an effect and influence on me, and I am required to mention this to them.

On the other hand, there is a very high risk here that negative motivations are actually what are encouraging the person to rebuke his friend. Many times, negative emotions involving personal jealousy are what cause us to rebuke our friends, and then instead of rebuking others in order to fulfill the mitzvah, in many cases, we end up humiliating and persecuting others, and this devolves into complicated and bitter conflicts. And all this is in the name of “the mitzvah of rebuking others.”

The Torah emphasizes that even when you rebuke your friend, you need to be careful that because of your rebuking him, “you shouldn’t bring a sin upon yourself,” which is what would happen were you to embarrass him in public!

This is why the Torah mentions the mitzvah of rebuke together with the mitzvah of not embarrassing one’s friend in public. Despite the mitzvah to rebuke others, one must be very careful that his motives are not for personal reasons like hatred, G-d forbid. All the more so, he must be careful not to cause machloket when he fulfills the commandment to rebuke.

The Gemara teaches: “Rabbi Akiva said: I wonder if there is anyone in this generation who knows how to rebuke properly.” Rashi explains the meaning as: “if there is any person who knows the proper way to give rebuke, so that he will not have it counted against him as a sin and also not embarrass the other person.” The Gemara points out a paradox here: Which is preferable—to rebuke “lishmah” (for pure reasons and the sake of Heaven), with the right intentions so that the other person will come closer to the truth, or to have humility which is not “lishmah,” absolving oneself of the mitzvah of rebuke because it is uncomfortable for him to rebuke another person because he suspects that perhaps he is doing it out of hatred, and explaining his desire to refrain from giving rebuke as his being humble and unfitting to give others rebuke? The conclusion in the Gemara is that “humility that is not lishmah is better than rebuke which is lishmah” (Arachin 16b).

In many cases, we end up humiliating and persecuting others…

We frequently see those who try to humiliate the G-d-fearing and scream at them in anger. This is the exact opposite of the truth, and instead of appreciating them and their mesirut nefesh (self-sacrifice) in serving G-d, they dismiss and laugh-off such service as phony and counterfeit. They permit themselves every kind of unconstrained behavior in order to give their rebuke.

Rabbi Natan points out that many communities were destroyed because of machloket. In fact, were it not for the severe degree of machloket that exists, in the end, everyone would come close to the tzaddikim and return to the straight path, no matter how bad their misdeeds are. The main problem is due to the machloket which occurs when people disregard the opinions of entire communities, which then cause the masses and even the good people amongst them to disqualify the opinions of tzaddikim because they have found some “sin” in them, which in their opinion they are not doing right, which is all the “proof” they need that they are not behaving correctly. Instead of discussing it with them, they promote accusations against them, which in turn, distances the public from them. Thus, the Chassidic communities in the past, who emerged as a legacy of the disciples of the Baal Shem Tov at that time, were systematically disqualified in the name of the mitzvah of rebuke. They were publicly humiliated, and any positive influence they could have had was nullified. All this was done by those who were on fire to rebuke, without ever thoroughly examining the facts, and so it is in every generation.

Rabbi Natan adds that if Rabbi Akiva said such things about his own generation, how much more so is it true regarding our generation, and it is something we have to be very careful about. Certainly, it is a great mitzvah to speak to our friend and incline his heart toward the proper path, but G-d forbid we should come to embarrass him, especially in public because of his deeds. All the more so, must we be careful not to incite or awaken any controversy against him. In the words of Rabbi Natan: We have 613 mitzvot from Moshe Rabbeinu; we have no need to add any new ones (i.e., of making machloket.)

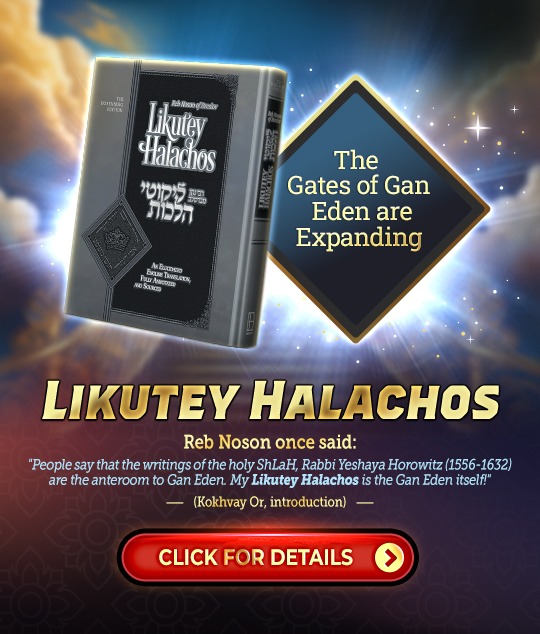

(Based on Likutei Halachot, Yayin Nesech 4:13-18)

- Chassidic communitiesDvar Torah for Parshat Kedoshimembarrassingembarrassing in publicemunahfaithfeaturedhumiliatinghumilityinspirationJewish spiritualityjoyKedoshimlaws of the TorahLikutey Halachotmachloketmesirut nefeshparadoxParshaParshat Kedoshimrabbi akivaRashiReb NosonRebbe Nachmanrebukeself-sacrificeTen CommandmentsTorahTorah’s commandmentstruthTzaddikzealous

- 0 comment