ADAPTED FROM ONE OF HIS AUDIO SHIURIM

Learning from history

Rebbe Nachman states very clearly that any Jew can discover himself in studying the history of our people – the wars, the challenges, the failures and the successes. The continuous rise and fall of our people repeats itself in the life of every single Jew, even several times in a single day. A Jew might find that in the morning he goes to shul and davens with a lot of kavanah, only to forget himself once he is steeped in his business dealings. Then he neglects his real mission in life – to serve HaShem – only to be reminded again suddenly that there is something more vital, more important, to live for. This is the ebb and flow of the Jew’s spiritual life: losing one’s perspective and then renewing one’s spirit so as to rise again and be accepted by HaShem. Just like the cycles that we find in the history of our people.

If one wants to know which direction to take in life, one need only study the history of our people and apply the same advice that HaShem gave in the past to one’s own situation. If you need a better job, do not turn to the want ads – turn to HaShem. If you want to improve your income, go to shul, take out a Tehillim and pray to HaShem. If your prayer is sincere, you will find that somehow a light will begin to shine from somewhere. You may never have suspected it would come from there but it suddenly does, only through HaShem’s blessing.

Ehud ben Gera

When Benei Yisrael found themselves oppressed by Eglon, the king of Moav, they turned to HaShem, prayed to Him intently and He heeded their cries. He sent them another savior, another shofet whose name was Ehud ben Gera. Ehud was also a tzaddik, a fitting judge and a courageous and talented military commander. Ehud, being left-handed, hid his dagger on his right thigh beneath his garment. When he asked to speak with the king in private, he bared his left thigh to show him that he had no weapon. The king acceded to his request and after they entered the king’s private chamber, Ehud said to him, “I have a word of God for you” (Shoftim 3:20). Although a heathen, upon hearing the Name of God Eglon stood up out of respect. As he did, Ehud suddenly drew his dagger and plunged it into Eglon’s belly. Once a king is killed, the morale of his army naturally plummets to a point where it is severely weakened. Ehud quickly mobilized Benei Yisrael and they attacked the army of Moav, killing over 10,000 soldiers. Indeed, Moav actually became subservient to Yisrael and the land remained peaceful for eighty years.

Giving kavod to HaShem

The Gemara (Sanhedrin 60a) teaches that a vital lesson may be learned from this story. Eglon was a non-Jew, a heathen goy, and yet when he was about to be presented with the word of HaShem he stood up out of respect. How much more so is it incumbent upon us Jews, who live so as to honor HaShem, to stand when we hear His Name pronounced, such as during the Kedushah or the recitation of Kaddish. One must similarly give honor by answering amen whenever one hears a berakhah. If one neglects to, especially if it is due to his engaging in idle talk, both the Gemara and the Zohar HaKadosh state that he deserves to be stricken dumb, chas vesholom.

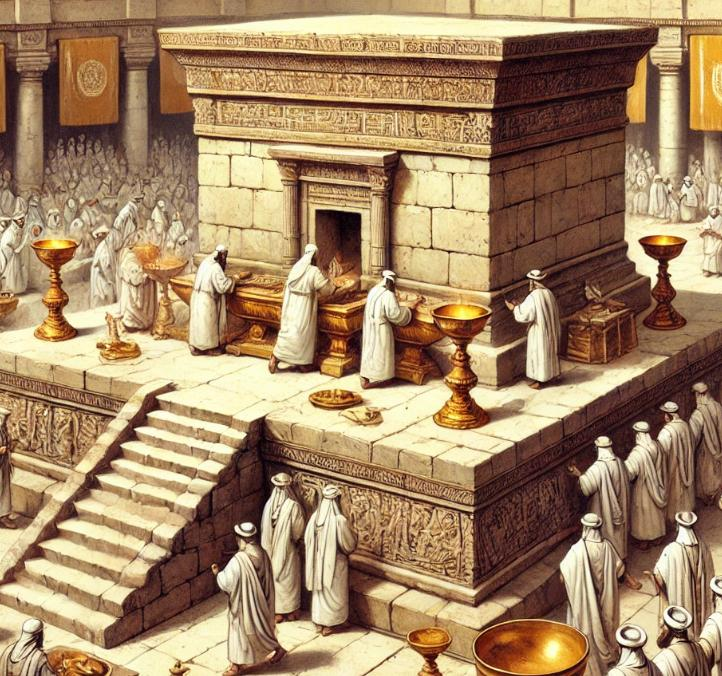

Korban: Drawing Close to HaShem

Indeed, saying these words actually expedites the coming of Mashiach. When HaShem destroyed the Beis HaMikdash and drove us into exile, He forfeited the great pleasure of having His children with Him in His own home and at His own table. For when we brought a todah or shelamim sacrifice in the Temple, the meat was partly enjoyed by HaShem on the mizbe’ach, the altar, and partly enjoyed by the one who brought it. That is why it was called a korban – because it was mekarev, it “brought one close” to HaShem through sharing the offering. But then HaShem drove us from His “table.” Still, no matter how badly one’s children act, one cannot bear the separation from them. The same holds true, as it were, with regard to HaShem. Though despondent over the exile of His children, He is bound by His own vow not to end the galus before its appointed time. The Midrash (Otzar HaMidrashim, Gan Eden p. 86) states that every time we go to shul and respond yehei shemei rabbah mevorakh le’olam ul’olmei olmaya to the Kaddish, HaShem, as it were, sheds tears that shake all of Creation. HaShem cries over the fact that His children are in galus and yet they still exalt His Name. Those tears of HaShem add up and hasten the ge’ulah, the coming of Mashiach; all in the merit of Yehei shemei rabbah.

The Kaddish is so holy that it is referred to as devar HaShem, the word of HaShem (Hagahos HaMordechai, based on the Yerushalmi. See Magen Avraham on Orach Chaim 56:1). A person who refuses to stand and say yehei shemei rabbah when it is being recited is guilty of showing less respect for HaShem than that slovenly king, Eglon, when confronted by Ehud! That ugly oppressor of Benei Yisrael had more respect for HaShem than the lazy Jew sitting in shul. That is why the Gemara and the Shulchan Arukh are so adamant in this regard. One need only enter any shul and observe how widespread the problem is! When Kaddish is being said, how many people in shul stand up for it? More so, look at how many do not even pay attention to it! Aside from remaining seated, they do not even bother saying amen or yehei shemei rabbah. This neglect in no way reflects on the importance of the Kaddish. On the contrary, it shows how holy it is; that is why the yetzer hara works so hard to have Jews ignore it, thereby prolonging the galus and extending the satan’s reign. Once the galus is over, the satan is wiped out. This is a battle between us and the satan, between tumah and kedushah. We must see that kedushah prevails and that respect for HaShem remains solid by properly responding to Kaddish. This may be a small gesture, but it is vital, and as great as the punishment is for neglecting it, such is the reward for observing it. The Zohar (Zohar Devarim 286a) states that there are special sections set aside in Heaven for those who are careful to answer amen to the Kaddish and other berakhos with all their might. All their might means with all their kavanah, their pure concentration.